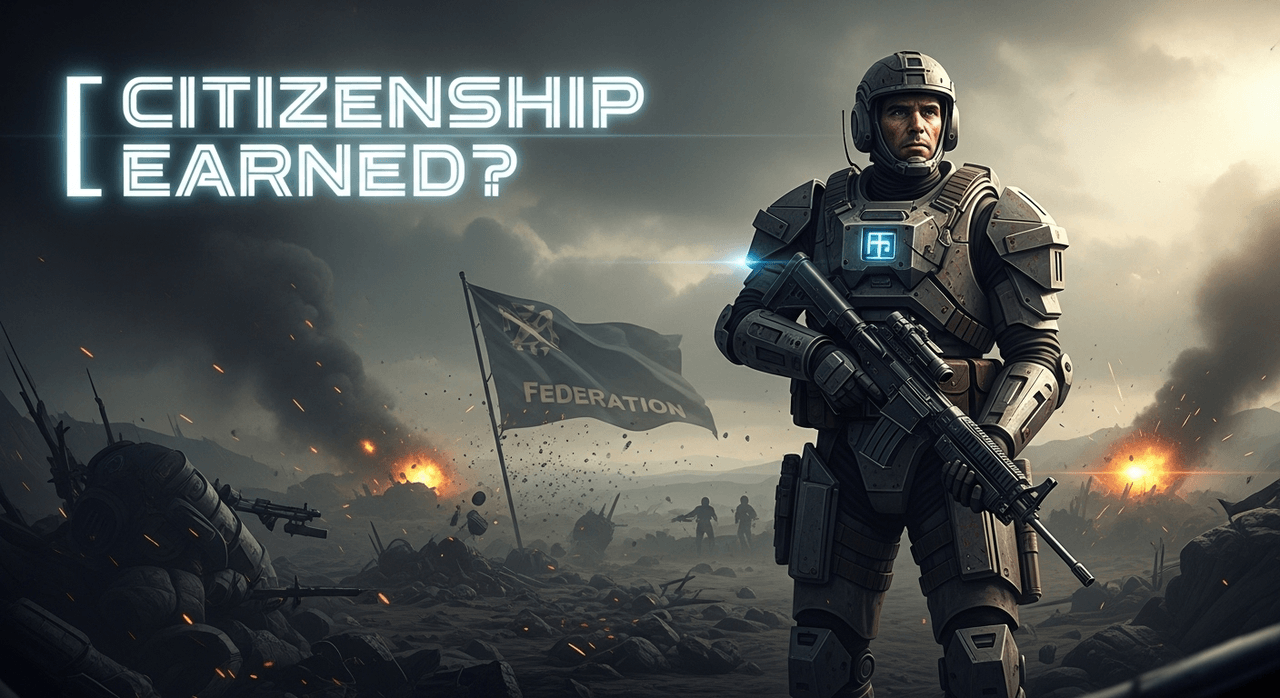

I still remember my first brush with Starship Troopers: not the explosive movie, but the dog-eared paperback on my uncle’s shelf. I was only interested because the cover promised cosmic warfare. What I got, instead, was a head-scratcher about who should vote and what you should have to do to deserve it. Turns out, the book has a way of sneaking under your skin—making you question things you never thought to question, like why political power should be earned at all. If you’ve ever wondered whether voting is a right, a privilege, or something trickier, buckle up—the world of Starship Troopers has a few curveballs for you.

When the Dust Settles: The Battle of Clandathu and What It Sets in Motion

“ 30 years ago, the Battle of Clandathu was fought on this very ground. The single greatest military catastrophe in the history of the Federation. ” These words, echoing at the start of Starship Troopers , do more than set the scene. They anchor the story in a collective trauma, one that shapes not only the characters but the entire society. The Battle of Clandathu significance is not just military—it's political, social, and deeply psychological.

Clandathu: More Than a Failed Battle

Clandathu is remembered as a legendary disaster. The Federation’s forces, confident and unprepared, are decimated by the Arachnids. In the aftermath, the ground is empty—“not a bug in sight”—but the scars remain. This isn’t just a military loss; it’s a national wound. The memory of Clandathu justifies the Federation’s iron grip on its citizens, and it becomes the story’s launching pad for bigger questions about power, fear, and who gets to belong.

Why Open With Catastrophe?

Why does Heinlein open the book here? The answer is simple: catastrophe changes everything. When a society faces a loss of this scale, the rules can shift overnight. The Battle of Clandathu significance lies in how it reframes what the Federation values. The trauma of defeat becomes the rationale for exclusive citizenship and strict military service requirements. The Federation’s leaders point to Clandathu as proof that only those who have risked everything for the state should have a say in its future.

Political Commentary: Catastrophe as Justification

This is where Starship Troopers political commentary comes into focus. The Federation’s response to Clandathu is draconian by our standards, but not so unthinkable after trauma. Imagine your own country suffered a loss so devastating that its very survival seemed at stake. Would you accept new rules about who votes or gets to lead? Would you trade some freedoms for a sense of security? Heinlein’s world says yes—at least, that’s the logic the Federation uses.

- Clandathu as a filter: The disaster becomes a filter for citizenship. Only those who serve—who prove their willingness to sacrifice—are trusted with political power.

- Fear and unity: The shared memory of loss binds the society together, but also narrows the definition of who counts as a “citizen.”

- Justifying authority: The Federation’s authority is rooted in the idea that catastrophe demands discipline and sacrifice, not debate or dissent.

Service, Citizenship, and Exclusion

Heinlein’s political philosophy is clear: military service acts as a filter for enfranchisement, linking civic virtue and political power. But the book also quietly questions this system. In one scene, Rico and his friends, on liberty near Vancouver, meet merchant marine sailors. These sailors resent the Mobile Infantry, not because they are lazy, but because their own dangerous service is not recognized as “federal service.” Their guilds have tried to get their trade classed as equivalent, but without success.

This echoes real history. During World War II, thousands of merchant marines risked—and lost—their lives delivering military goods into hostile territory. Yet, they were not recognized as veterans until the mid-1980s. The Federation draws a hard line: military service counts, civilian service does not. According to Heinlein’s extended universe, 19 out of 20 “veterans” are not traditional infantry, but the principle stands—service is the price of citizenship.

“Merchant sailors are civilians. The merchant marine, as the name implies, deals with mostly commercial shipping. However, in wartime, they could be called upon to deliver military goods into hostile territory, essentially as a support arm of the Navy. In our own history, thousands of merchant sailors died in World War II in that capacity of supporting the US military. Those men were not recognized as war veterans.”

Clandathu’s Legacy: Fear, Power, and Belonging

The Battle of Clandathu significance is not just in the numbers lost, but in how it shapes the Federation’s rules about who gets to belong. The trauma of defeat becomes the justification for a society built on exclusion, discipline, and sacrifice. The memory of Clandathu lingers, not just as a warning, but as a foundation for the Federation’s vision of citizenship—and a challenge to our own ideas about who deserves a voice.

Military Boot Camp or Civics Classroom? The Price of Political Power in Starship Troopers

When I first read Starship Troopers , I pictured space boot camp as all push-ups and laser drills. But Heinlein’s world throws recruits into a much deeper philosophical gauntlet: only those who serve—through military service—earn the right to vote. This isn’t just about who’s the bravest or most disciplined. Heinlein’s idea of citizenship responsibilities is about proving you can sacrifice for the greater good, not just yourself. The price of political power is paid in sweat, discomfort, and sometimes danger. There’s no free ride, and certainly no shortcuts through civilian jobs.

Military Service and Citizenship: The Only Clear Route

There’s a long-running debate over whether Heinlein’s novel depicts a society where military service and citizenship are inseparable, or if any broadly defined federal service qualifies. But the book itself is pretty clear: military service is the single path to enfranchisement. Heinlein uses the word “veteran” specifically and repeatedly. In one telling scene, Rico and his fellow Mobile Infantry recruits run into merchant marine sailors near Vancouver. The merchant marines resent the soldiers, because their trade guilds have tried and failed to get their own service recognized as equivalent to federal service. In Heinlein’s world, merchant sailors are civilians—no matter how dangerous their jobs might get in wartime.

This distinction matters. Even though, in our own history, merchant mariners risked—and lost—their lives delivering military goods in World War II, they weren’t recognized as veterans until decades later. In Starship Troopers , Heinlein makes it explicit: the merchant marine does not count as federal service. The same goes for other civilian roles, like DoD clerks or postal workers. If you want political power, you have to serve in a way that’s militarized, even if you end up in a non-combat role like a cook or labor battalion.

Boot Camp as Civics Classroom: Indoctrination and Sacrifice

What struck me most on rereading is how Rico’s officer training is as much about philosophy as it is about tactics. The required “History and Moral Philosophy” courses aren’t just filler—they’re central to molding a special voting class. The instructors don’t just teach how to fight; they teach why the right to vote must be earned through sacrifice. It’s a form of indoctrination, but also a civics lesson: authority comes only after you’ve proven you’re willing to put the group above yourself.

“You and I are not permitted to vote as long as we remain in the service. Nor is it verifiable that military discipline makes a man self-disciplined once he is out.”

This quote underlines the idea that even military discipline isn’t a guarantee of good citizenship. The system is designed to weed out those who can’t handle discomfort or danger—whether that means the physical rigors of boot camp or the moral weight of responsibility. Some, like the older recruit Kurthers, simply can’t keep up physically, no matter how hard they try. But even for those who fail, the service is still militarized. There’s no “easy” federal service track for the unfit; everyone faces the same gauntlet.

Heinlein’s Contradictions: Federal Service Citizenship Criteria

Here’s where things get messy. Decades after the novel’s publication, Heinlein himself muddied the waters by claiming that “veteran” doesn’t always mean military. In a 1980 essay, he wrote, “Veteran does not mean in English dictionaries or in this novel solely a person who has served in military forces... no one hesitates to speak of a veteran fireman or a veteran school teacher.” He even claimed that 95% of voters in his universe were former members of federal civil service, not military veterans.

But the text of Starship Troopers doesn’t really back this up. The book specifies, more than once, that only military service counts for citizenship. Civilian roles, even those adjacent to the military, are excluded. This contradiction between Heinlein’s later statements and the novel’s content is a big reason why military service enfranchisement remains controversial. Some readers want to see the book as promoting fascism or militarism; others try to soften its message by arguing for a broader definition of service. But the story itself is clear: not everyone gets a say in how society is run. Only those who have proven their willingness to sacrifice through military service are trusted with political power.

Vote if You’ve Earned It—Or Not at All: Civic Virtue, Responsibility, and Who Decides

One of the most striking ideas in Starship Troopers is how it flips the usual debate on voting rights and political power. In Heinlein’s world, not everyone automatically gets a say in how society is run. Instead, the Federation limits political power to those who have proven themselves—those who have demonstrated civic virtue through service and sacrifice. This is the heart of Heinlein’s civic virtue argument: voting is not a birthright, but a responsibility that must be earned.

In the novel, citizenship—and with it, the right to vote—is explicitly tied to federal service. This isn’t just about military combat. The book makes clear that there are “hostile and dangerous, thoroughly unpleasant alternatives for those unfit for regular military service in any capacity.” Even if someone can’t serve on the front lines, they might be assigned to a cook’s job on a troop transport, as happened to Kurthers, an older recruit who physically couldn’t keep up but refused to quit. The point is, the service must be direct and meaningful, not just a symbolic gesture or a cushy government job. The system is designed to test commitment, endurance, and willingness to put the community above oneself.

This approach to voting rights and military service is a sharp contrast to our own. Today, disenfranchisement is seen as a grave injustice—a crisis to be solved. But in the Federation, it’s the default. Only those who have completed their service are trusted with the power to direct the state. Heinlein’s system is not about excluding people for the sake of exclusion, but about self-selection: only those willing to endure hardship for the public good are allowed to wield political power. As the book says, “voting is not about having a voice, but about directing state force.”

This idea is rooted in a long tradition of civic virtue in political philosophy. John Adams famously said, “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.” Heinlein’s twist is to ask: what if, instead of hoping citizens are virtuous enough to sustain democracy, we only allow those who have proven their virtue to participate at all? In the Federation, morality and religion are replaced by forethought and responsibility. The right to vote is not inherited, but earned through action and sacrifice.

The process is not just about service, but about shaping citizens. Rico’s journey through officer training includes a history and moral philosophy course that he must pass to his instructor’s satisfaction. Failing isn’t just about not becoming an officer; it can mean losing the chance to be a citizen at all. The system is designed to “temper the politically active class,” ensuring that those who hold power have demonstrated the responsibility and restraint needed to use it wisely. The uncommitted and the genuinely unfit are filtered out—not by accident, but by design.

This raises uncomfortable questions for us. Would we ever accept a system where the right to vote required years of difficult, sometimes dangerous service? What if our own ballot box demanded not just citizenship by birth, but proof of sacrifice and commitment to the common good? Heinlein’s Federation is a world where enfranchisement is not a right, but a privilege earned through hardship. It’s a radical answer to the debate on political rights—a world where the default is disenfranchisement, and only the most responsible are allowed in.

In the end, Starship Troopers is less about glorifying military service and more about challenging us to rethink what it means to be a citizen. Heinlein’s civic virtue argument is clear: power must be earned, not inherited. The right to vote is recast as a responsibility, not a reward. Whether we agree with this vision or not, it forces us to confront the foundations of our own democracy—and to ask who should decide who gets to decide.